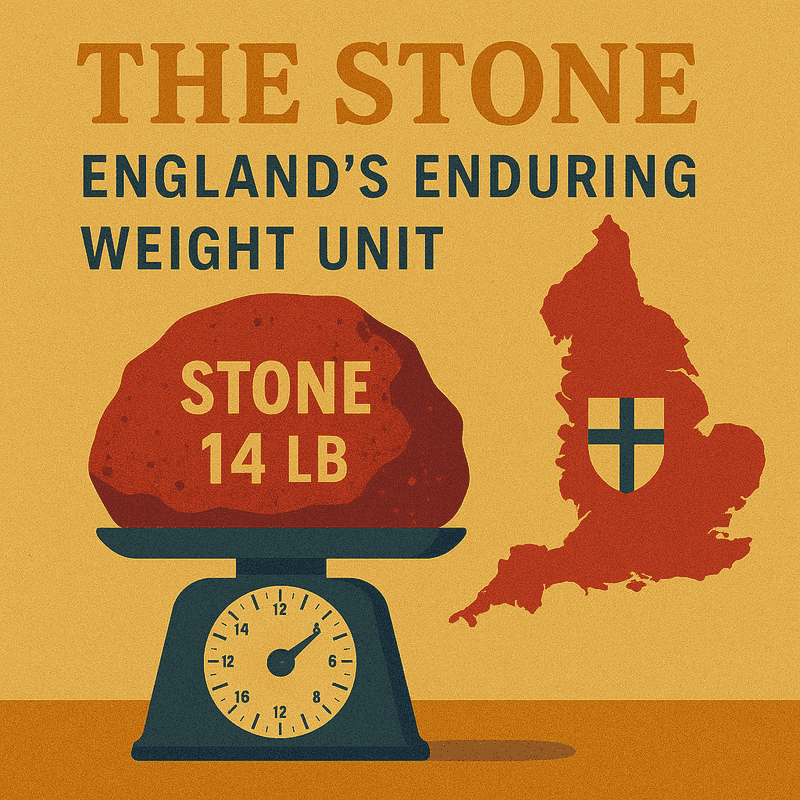

In a world increasingly governed by the International System of Units (SI) and its standardized metric measurements, one curious anomaly persists primarily in the United Kingdom and Ireland: the stone. This unit of weight, equal to 14 pounds (6.35 kilograms), continues to be widely used for measuring human body weight despite official metrication efforts spanning decades.

The stone represents a fascinating piece of living history—a measurement that has survived from ancient commerce to modern bathroom scales, defying both international standardization and government policy. But where did this peculiar unit come from, and why does it endure in British culture when most other traditional measurements have faded into history?

Ancient Origins

The concept of using stones as weights dates back to antiquity. The very word "stone" reflects the practice's ancient origins—actual stones were among the earliest tools used for weighing goods in marketplaces across civilizations. Archaeological evidence shows stone weights being used in trade throughout the ancient world, from Mesopotamia to Egypt and beyond.

References to stone weights appear in some of history's oldest texts. The Book of Deuteronomy in the Bible contains prohibitions against carrying "diverse weights, a large and a small," which in original Hebrew more literally translates to "you shall not carry a stone and a stone, a large and a small." This reference highlights both the antiquity of stone weights and early concerns about standardization and fair trade.

By Roman times, stone weights were crafted to specific multiples of the Roman pound. Archaeological museums today hold examples of these weights crafted from various materials, including polished serpentine and sandstone, demonstrating the evolution from rough stones to carefully crafted measurement tools.

The Medieval Stone

Throughout medieval Europe, units called "stone" (German: Stein; Dutch: steen; Polish: kamień) were used across various regions. However, the actual weight these represented varied widely—not just between countries but even between cities and commodities. A stone used for weighing wool might differ significantly from one used for precious metals or foodstuffs.

In England, this variation was particularly pronounced. By the 13th century, different stones were used for different commodities. The Assize of Weights and Measures, a statute from around 1300, described stones of varying weights: 5 pounds for glass, 8 pounds for beeswax and spices, 12 pounds for lead, and the "London stone" of 12½ pounds for wool.

King Edward III attempted to standardize this chaos in 1350 by issuing a statute defining the stone at 14 pounds, specifically for wool and "other Merchandizes." This definition was reaffirmed by Henry VII in 1495. However, regional and commodity-specific variations persisted for centuries afterward.

A Patchwork of Stones

Even after Edward III's standardization attempt, the actual weight of a stone remained highly variable depending on what was being weighed. The following are just a few examples of the different stone weights used in England:

- Wool: 14, 15, or 24 pounds

- Beef and mutton: 8 pounds

- Sugar and spices: 8 pounds

- Wax: 12 pounds

- Lead: 12 pounds

- Glass: 5 pounds

This commercial pragmatism led to some ingenious practices. For instance, live animals were weighed in stones of 14 pounds, but once slaughtered, their carcasses were weighed in stones of 8 pounds. This convenient ratio allowed butchers to return dressed carcasses to animal owners "stone for stone," keeping the offal, blood, and hide as payment for slaughtering and dressing the animal.

London's famous Smithfield Market continued to use the 8-pound stone for meat until shortly before the Second World War—a remarkable persistence of medieval commercial practice into the 20th century.

The Path to Standardization

The Weights and Measures Act of 1824, which established the imperial system of units for the entire United Kingdom, consolidated centuries of measurement legislation. While it revoked provisions regarding wool being sold in stones, it made no specific provisions for the continued use of the stone as a weight unit.

A decade later, stones still varied widely in practice, from 5 pounds for glass to 14 pounds for what was called "horseman's weight" (the weight carried by racehorses). The Weights and Measures Act of 1835 finally permitted using a stone of 14 pounds for trade, officially standardizing the measurement.

Despite this legislation, local variations persisted well into the 19th century. As late as 1880, different values of the stone were documented in various British towns and cities, ranging from 4 pounds to 26 pounds.

The Modern Stone

The 20th century brought significant changes to Britain's measurement systems. In 1965, the government announced a voluntary ten-year metrication program. Under the guidance of the Metrication Board, the agricultural product markets achieved a voluntary switchover to metric units by 1976.

The Weights and Measures Act of 1985, which implemented European Union directives, officially abolished the stone as a unit of measurement for trade. However, the act specifically permitted the continued use of the stone for weighing people and animals, recognizing its deep cultural significance.

This legislative compromise reflects the stone's unique position in British culture. While officially "abolished" for commercial purposes, it remains legal and widely used for personal weight measurement. This dual status—both officially recognized and officially abolished—perfectly captures the stone's paradoxical nature as a measurement unit.

Cultural Persistence

The stone's continued use in Britain is a remarkable example of cultural persistence. Despite decades of official metrication efforts, the stone remains the preferred unit for discussing human body weight in everyday conversation. Ask a British person their weight, and they're far more likely to say "12 stone" than "76 kilograms."

This cultural attachment extends beyond casual conversation. British media routinely report weights in stones, particularly for celebrities, athletes, and public figures. Medical professionals in Britain often record patient weights in both stones and kilograms, accommodating both traditional preferences and international standards.

The stone's persistence also reflects broader patterns in British society's relationship with measurement systems. While Britain has officially adopted the metric system, many traditional units continue in everyday use. Road distances are measured in miles, beer is sold in pints, and human weight is measured in stones. This hybrid approach reflects a pragmatic British attitude toward change—adopting new systems where they make sense while preserving traditional units where they remain culturally meaningful.

The Stone Today

Today, the stone continues to thrive in British culture despite its official abolition for trade. Digital bathroom scales commonly offer readings in both stones and kilograms, and fitness apps and health tracking devices routinely include stone measurements. The unit's continued relevance is evident in its widespread use across all age groups and social classes.

The stone's survival also highlights the importance of cultural factors in measurement systems. While the metric system offers undeniable advantages in terms of consistency and international communication, traditional units often carry cultural and emotional significance that transcends their practical utility. The stone represents a connection to Britain's medieval past, a reminder of the country's long history of trade and commerce.

In many ways, the stone embodies the British approach to tradition and modernity—respecting the past while embracing the future, maintaining cultural continuity while adapting to changing circumstances. Its continued use represents not resistance to change, but rather a thoughtful integration of old and new, tradition and progress.

As Britain continues to navigate its relationship with the European Union and global standards, the stone serves as a reminder that measurement systems are not merely technical tools but cultural artifacts that reflect the values, history, and identity of the societies that use them. The stone's enduring presence in British life suggests that some traditional measurements may continue to coexist with international standards for generations to come.